Nearly 17 years ago, Dr. Mark Hoofnagle coined a term, crank magnetism, to describe how believers in one form of pseudoscience, quackery, and conspiracy theory almost inevitably start believing in multiple forms of pseudoscience, quackery, and conspiracy theories. At the time, he was discussing how creationists were attracted to the arguments of HIV/AIDS denier Peter Duesberg because they thought that these arguments somehow also undermined evolution as well. Back around the same time, inspired by Dr. Hoofnagle’s term, I noticed so many more examples. I’ll cite a few, not so much because readers might be familiar with them (although some longtime readers might), but just to show that crank magnetism, as new as it might seems to so many of my colleagues who had never noticed it before, is, in fact nothing new:

For example, Phillip Johnson, one of the “luminaries” of the “intelligent design” creationism movement is also a full-blown HIV denialist who doesn’t accept the science that demonstrates that HIV causes AIDS. Another example is Dr. Lorraine Day, who is heavily into dubious alternative cancer therapies and is also a conspiracy theorist and Holocaust denier. More recently a creationist, Johannes Lerle, was jailed as a Holocaust denier in Germany, and crank supreme Larry Fafarman proudly claims himself to be a “Darwin doubter” and a “Holocaust revisionist.”In a similar vein, antivaccinationist Pat Sullivan, Jr. is also a “Darwin doubter,” while regular contributor at Bill Dembski’s home for ID sycophants Dave Springer (a.k.a. DaveScot) not only rejects the science of evolution in favor of the pseudoscience of ID, but is also a global warming denialist crank and encourages unsupervised experimentation with an unproven anticancer agent by desperate cancer patients.

Sound familiar? (As an aside, I also note that, until I started checking out all those links to make sure they were still live or to substitute Archive.org or more up-to-date links, I hadn’t known that Dr. Day had passed away last November.)

A specific subset of crank magnetism applies to quacks and the antivaccine movement, examples of which I’ve discussed fairly recently in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic antivaccine movement, which has embraced “repurposed” drugs like hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin, and fenbendazole as supposedly highly effective treatments for COVID-19. (They are not.) Specifically, I’m referring to the manner in which increasingly believers in these drugs have “discovered” that they can use them to treat all manner of diseases, including cancer. For example, a year ago I noticed Dr. Tess Lawrie, a founder of the British Ivermectin Recommendation Development (BIRD) Group, a group that had teamed up with the US group the COVID Frontline COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance (FLCCC) to vigorously promote ivermectin as a highly effective treatment for COVID-19 despite all evidence to the contrary (including basic pharmacokinetics), starting to make the false claim that ivermectin could cure advanced cancer; that is, before she went on to embrace homeopathy for COVID-19 and long COVID. It didn’t take me long to quip that ivermectin was becoming the new Miracle Mineral Solution, a.k.a. MMS, given that quacks soon started treating autistic children with it, using it as yet another bit of quackery in their “autism biomed” toolkit.

The point, besides my oft-repeated mantra that “everything old is new again,” is that inevitably the embrace of one quackery will lead to the embrace of others, but the corollary to this that I want to talk about now is how there is always an “indication creep” for quackery. Once quacks “discover,” for instance, that ivermectin “treats COVID-19,” it is never long before they start “discovering” that it can treat all manner of diseases until it becomes a cure-all. This is a phenomenon that has accelerated with a vengeance for fenbendazole, which I first saw popping up not that long ago in ivermectin-like stories of “cures” for COVID-19 but is now a full-blown quack “cancer cure” being promoted everywhere. In particular the odious blogger 2nd Smartest Guy in the World (2SGitW) has been using his Substack to convince his readers that fenbendazole is a miracle cure for advanced cancer, complete with “miracle cure” testimonials. Unfortunately, though, he is not alone.

Let’s start with the article that caught my attention over the weekend, Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Eradicated by Fenbendazole, in which 2SGitW brags, “Fenbendazole kills the cancer cells responsible for killing cancer patients.” As I learned, it’s a followup to a cancer cure testimonial published a week earlier on the Substack in which 2SGitW massively exaggerated the the significance of some promising preclinical and lab studies suggesting that fenbendazole might have anticancer activity against triple-negative breast cancer written by someone going under the ‘nym of BenFen, who claims to be a “retired University scientist who happened across fenbendazole when a loved one developed terminal cancer” and runs a Substack that publishes cancer cure testimonials due to fenbendazole.

More interestingly, it turns out that fenbendazole repurposing has been a favorite “alternative cancer cure” since at least 2017, if not earlier, but the rise of ivermectin and other dewormers as “cures” for COVID-19 resurrected fenbendazole as one of the most favored unproven drugs being sold as cures for cancer in the age of the pandemic.

Fenbendazole versus triple negative breast cancer?

This particular article caught my attention because I have long been writing about how alternative cancer cure testimonials mislead, but even more so because it involves my area of surgical specialty and research interest, breast cancer. Before I discuss the testimonial, let me just review what “triple negative” breast cancer is and how it is normally treated, so that you can see the contrast and perhaps spot the common misleading part of this particular testimonial.

When we characterize breast cancer clinically, pathologists look at three different markers that guide systemic drug therapy used in combination with surgery and radiation therapy to treat it. The following is somewhat simplified (but hopefully not too much so). The first two are the hormone receptor proteins for estrogen and progesterone, which roughly two-thirds of breast cancers make, rendering them responsive to these hormones for growth. More importantly, the presence of these receptors means that the tumor can be treated with targeted endocrine therapy that blocks estrogen using drugs such as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like tamoxifen or drugs that block the production of estrogen, such as aromatase inhibitors. The third marker is HER2, an oncogene that is amplified in a subset of cancers. When a cancer is HER2-positive, it can be effectively treated with drugs that target HER2, such as trastuzumab (Herceptin®), usually also with chemotherapy.

What makes triple negative cancer so problematic is that it lacks any of these three markers, which means that targeted therapy is not possible. Moreover, triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) tends to be more aggressive, metastasize to bone, brain, lung, and liver, and recur earlier after treatment than hormone receptor-positive varieties. In general, before about four years ago, the only systemic treatment that was effective against TNBC was standard cytotoxic chemotherapy with a regimen called ACT (Adriamycin-Cytoxan-Taxol). However, after the KEYNOTE-522 trial was published in 2020, the standard of care for TNBC rapidly changed to include not just chemotherapy but immunotherapy with pembrolizumab (Keytruda®). In brief, the standard of care for most “curable” TNBCs (e.g., TNBC that has not spread to distant organs) is the KEYNOTE-522 regimen; i.e. neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy, usually with Taxol or another taxane with carboplatin, plus pembrolizumab, with the pembrolizumab being continued after surgery for a total of a year. It is a regimen that has pushed pathologic complete response (pCR) rates to well over 60%, and pCR correlates with improved survival. (A pCR occurs when there are no detectable viable tumor cells in the resected specimen.) In brief, the KEYNOTE-522 regimen is the most significant improvement to the treatment of women with TNBC that I can recall since I started my career as a breast cancer surgeon in the 1990s.

With that background on how TNBC is normally treated in 2024, let’s look at the anecdote, which was also published earlier on BenFen’s Substack, Fenbendazole can cure cancer. First, though, I’m going to point out that the blurb after the title is a hint:

No Chemotherapy or Radiation; Fenbendazole Only = Full Remission

See where this is going? Once again, this is an example of how these testimonials often leave out critical information. Let’s take a look, where BenFen starts out with mostly accurate information before the misleading narrative takes off:

This Case Report is from a 45 year old woman with metastatic Stage III triple-negative breast cancer that had spread to nearby lymph nodes. According to the Cleveland Clinic, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an especially dangerous form of invasive breast cancer, accounting for 15% of all invasive breast cancer cases. Unlike most breast cancers, triple-negative breast cancer cells don’t have receptors for estrogen and progesterone. Because this type of breast cancer doesn’t have the hormone receptors used by the current drugs to attack most breast cancers, the prognosis is very poor using traditional treatments like chemotherapy. Recall that receptors are molecules on cells’ surfaces that determine what substances can attach to cells and affect what the cells do. Triple-negative breast cancer cells don’t have these receptors, so the traditional chemotherapies used to target breast cancer cells by their hormone receptors don’t work. So there is a dire need to find treatments that actually work.

Notice how the word “metastatic” is used. Here, BenFen is clearly trying to imply that this is an incurable cancer. However, by definition stage III is not incurable; rather, it is considered locally advanced and therefore potentially still curable. Moreover, while it is true that “traditional chemotherapies used to target breast cancer cells by their hormone receptors” don’t work against TNBC, the way this statement is phrased is misleading. We generally don’t call such treatments “chemotherapy.” Rather, we call them “endocrine” or “hormonal” therapy, as what is being discussed in this sentence are drugs like tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. I realize that pedants might try to counter that, yes, endocrine therapy is indeed a subset of chemotherapy if you mean the more general definition of “chemotherapy” in which it refers to any chemical/pharmaceutical therapy, but the use of the phrase in this manner was clearly intentional and meant to imply that chemotherapy doesn’t work. While the KEYNOTE-522 regimen is a major improvement in the treatment of TNBC, the chemotherapy regimen used before this study did work. It’s just that TNBC, by its nature, tended to develop resistance and recur; however, we still managed to “cure” large numbers of women with TNBC using the “old” regimen dating back decades.

Now, let’s look at the actual testimonial:

I was diagnosed with Stage III*, Triple Negative Breast Cancer in October of 2022 after noticing some changes on the skin of my breast and some pain in the area. Mammogram, CT scan and biopsy confirmed that it was breast cancer….triple-negative breast cancer. I had stage 3 triple negative breast cancer involving my lymph nodes, the worst one to get, and it (fenbendazole) worked for me.

The cancer had spread to the nearby lymph nodes and was causing the skin on my breast to discolor. I took Safe-Guard (fenbendazole [2SG: PetDazole is 3rd party tested pharmaceutical grade fenbendazole that is offered at a less expensive price-point]) for 14 weeks, started the 3 days on, 4 days off protocol that I read about for about the first 7 weeks. Then increased from 1 box a week (each box has 3 packets), to a box and a half (about 5 packets of 222 mg each) per week.

The first thing I noticed was my skin clearing up, the small spots on my breast disappeared at about 11 weeks after starting fenbendazole. This was the 222mg dose. No side effects at all.

My advice, take fenben, and don’t stop. At least not until it’s gone. I’ve been cancer-free for almost 16 months. Best of wishes to all of you!

L. K. T., Tucson AZ, December 5, 2023

I note that the “*” did lead to an admission that this was not stage IV cancer tacked onto the very end of the post:

*Stage III: At this stage, the cancer has spread beyond the point of origin. It may have invaded nearby tissue and lymph nodes, but it hasn’t spread to distant organs. Healthcare providers may use the term “locally advanced breast cancer” to describe Stage III cancer.

Now, let’s look at this in a bit more detail. Notice how LKT doesn’t mention at all whether she had surgery or not, but BenFen pointedly states “no chemotherapy or radiation” (emphasis mine). Surely, if the woman had not had surgery, BenFen would have included it in the blurb, given how advocates of unproven cancer therapies always like to emphasize the conventional treatments not used. I also noticed rather quickly that surgery was left out of the entire anecdote as well, which led me to wonder: What form did this “biopsy” take? Was it a core needle biopsy, which is the most commonly used form of biopsy for breast cancer now? A core needle biopsy, often guided by ultrasound or mammography, uses a large needle to take tissue cores from the tumor, leaving the tumor intact. In contrast, an excision biopsy removes the whole mass and can in some cases be curative by itself because the mass is removed. (Seriously, I’m getting acid flashbacks to my very early days discussing “cancer cure” testimonials nearly two decades ago.) In any case, most likely this women underwent surgery of some sort, refused chemotherapy and radiation therapy, and then attributed her good fortune to the fenbendazole rather than the conventional treatment. We can’t know, though, because the anecdote leaves out key information that would allow a reasonable assessment.

I wanted to find out more; so I started doing some Googling. I failed to find more on this women’s story, although there is a closed Facebook group that I encountered (Triple Negative Breast Cancer Fenbendazole) that might be hers, although probably not given that it appears to have been inspired by a 2016 story that showed me that the “repurposing” of fenbendazole for cancer goes back at least to 2017. So I perused some of the other testimonials on FenBen’s Substack. One recent testimonial reminded me very much of Chris Wark of Chris Beast Cancer fame, in which a stage III colorectal cancer was cured with surgery alone but the person making the testimonial attributed his good fortune to the quackery chosen, in this case fenbendazole. Another testimonial came from a woman with colon cancer metastatic to the liver. Of course, any surgical oncologist can tell you that it is possible to resect some liver metastases for colorectal cancer and produce long-term survival, and that’s what this woman appears to have undergone. She also underwent additional chemotherapy and surgery, with the tumors reportedly “returning,” although it is not said how they were diagnosed or whether they were ever biopsy-confirmed.

Yet another anecdote involved a patient adding fenbendazole to chemotherapy and radiation for esophageal cancer and then attributing the disappearance of the tumor to—you guessed it!—the fenbendazole, even going so far as to refuse the recommended surgery (esophagectomy) and then explicitly saying so:

Q: Do you think the chemo/radiation did the trick or was it the combination of chemo/radiation + fenbendazole?

A: I assume a combination but lean heavily toward the fenbendazole. Here’s why. The doctors were quite surprised (after the cancer was gone from their treatments). They wanted to do surgery after their chemo/radiation treatments to remove the esophagus and part of his stomach because they didn’t believe the chemo/radiation would get all the cancer. We refused the surgery. Esophageal cancer is very aggressive, I believe it didn’t spread beyond the one lymph node because we caught it early with fenbendazole.

Let’s put it this way. A pathologic complete response (pCR) due to neoadjuvant chemoradiation for squamous cell esphogeal cancer is far from unheard of, particularly for a tumor of the type described in the anecdote, specifically, with spread to a single regional lymph node. For example, this series quotes a pCR rate of over 40% for multimodality neoadjuvant therapy of squamous cell carcinomas of the esophagus. Basically, it was the chemoradiation that cured this patient, not the fenbendazole added to the regimen, but, as is typical, the patient attributed her good fortune not to the conventional therapy but to the unproven treatment chosen, conceding that, at most, it might have been the “combination” of the fenbendazole plus the conventional neoadjuvant therapy. I also note that for most cancers, achieving a pCR is associated with a much better prognosis. I further note that oncologists and surgeons are actively investigating whether patients who achieve what looks like a pCR after neoadjuvant therapy can safely forego surgery, and, if so, which patients.

Why are testimonials so convincing?

Basically, there are many reasons why alternative cancer cure testimonials are convincing. Indeed, let’s review a few common features of alternative cancer cure testimonials—hat tip to a longtime reader—that make them unreliable as evidence that the treatments tried had any effect:

- Misunderstanding of the natural history of cancer and survivorship bias. Some cancers, including colon cancer, can have a highly variable natural history. Remember that median survival means nothing more than that half of patients die before the median and half after. One example that I like to point out is a 1962 study of survival in women with untreated breast cancer at Middlesex Hospital in England from 1805-1933 that reported a median survival of 2.7 years, but a long “tail,” with a handful of survivors out as far as 15 years. Many times in these testimonials, the prognosis given (or heard) is far too pessimistic (e.g., “I was sent home to die”) and didn’t take into account the natural variability of cancer. In the cases of colon and breast cancer, for instance, our cancer institute has patients who have survived several years and are doing well. There’s a serious survivorship bias in these testimonials because, as I like to say, dead patients don’t give testimonials. Also, when they say the “doctor was amazed,” sometimes that is more of an indication of a doctor that is inexperienced with cancer than with an outcome far outside of the realm of the expected.

- Confusing adjuvant therapy for definitive therapy and misattributing their survival to quackery. There’s a whole subgenre of alternative cancer cure testimonials in which the patient giving the testimonial have undergone surgery for a solid tumor—again, commonly breast or colorectal—underwent curative surgery for the cancer but then refused adjuvant therapy, be it chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, immunotherapy, or radiation therapy in favor of whatever quackery they chose. (Examples include Chris Wark, Suzanne Somers, and many others.) Inevitably, if they survive they attribute their good fortune to the quackery, not to the definitive surgery that cured them, forgetting that the adjuvant therapy only decreases the chance of relapse after surgery and that surgery was what cured them. Sometimes, as Chris Wark did, they acknowledge this argument but then find a reason to claim that “surgery never cures patients like me.”

- Misdiagnosis by quacks. A number of alternative cancer testimonials feature failure to actually diagnose cancer by accepted methodology, substituting instead diagnoses by quacks using unscientific methodology that doesn’t include an actual tissue diagnosis from a pathologist.

- General vagueness. One thing. that I’ve learned dealing with alternative cancer cure testimonials like these is that I’ve been deconstructing fort two decades is that the testimonials are nearly always frustratingly vague from an oncological standpoint in a way that makes it very difficult to tell exactly what the patient had, how the tumor was treated, what the true stage actually was, and more. I’ve used my training as a surgical oncologist and cancer surgeon to infer from these testimonials what the true situation probably was, but one can never be sure.

- Old testimonials. Although fortunately this isn’t the case (yet) for any of these patients, often the ultimate outcome of these patients is death. However, testimonials often have an afterlife and live on, promoted by quacks long after the patient has died without a mention that the patient did ultimately die of cancer.

There are more features in addition to these, but when examining any alternative cancer cure testimonial, here are a few useful questions:

- Was the cancer still present when the alternative therapy was started? (Again, often surgery eliminated the cancer, and the patient is confusing cure with adjuvant therapy designed to decrease the risk of relapse.)

- Were all treatments disclosed? I forgot to mention above that often not all conventional treatments are described in these testimonials. Sometimes, I only find out that a patient had surgery by doing a deep Google dive to find all the appearances and interviews that I can, and even then I only find it mentioned in passing on social media posts by the patient.

- Was there ever a biopsy proving the existence of cancer? Were there reliable scans proving metastasis? You’d be surprised at how often the answer to one or both of these questions is no.

You will find many of these elements and questions in pretty much every fenbendazole testimonial presented, including one that hasn’t shown up on FenBen’s Substack (at least not as far as I’ve been able to tell) but did go viral earlier this year because it was featured on the podcast of comedian Jim Breuer.

But what about the science?

As is often the case with unproven treatments for cancer, advocates love to try to convince you that there’s lots of scientific evidence to support them and make the “miracle cure” testimonials more plausible. BenFen is no exception and apparently has used his background to try to summarize the evidence for fenbendazole as an anticancer agent. This is my territory too, as I have spent a number of years investigating whether the repurposing of an FDA-approved drug for another indication can result in effective treatments for breast cancer, and here’s what I can fairly say. There’s preclinical evidence in the form of cell culture studies and animal tumor studies that suggest that fenbendazole could have anticancer activity in humans. What I can also fairly say is that there is nothing in the preclinical evidence presented to suggest that, even if fenbendazole does have significant anticancer activity, it could ever be reasonably expected to produce the sorts of “miracle cures” described on his Substack.

FenBen starts out by summarizing a bit about what is known about cancer stem cells and then goes on to wildly over interpret the preclinical evidence for fenbendazole against breast cancer:

A recent 2022 study in the scientific journal Breast Cancer Research found that mebendazole (fenbendazole)1, a safe, readily available, inexpensive, side-effect free medicine that has had decades of favorable safety and efficacy data, prevents and eradicates triple-negative breast cancer and also prevents the development of metastases by reducing the likelihood of Cancer Stem Cells developing in distant regions.

Did you know that all cancer cells are not created equal? There is a process whereby cancer cells change, either due to treatments intended to help, genetics, and/or the passage of time (most likely an interaction of one or more above-named factors, and other factors yet to be identified), whereby cancer cells become more lethal (Brash, 2019 for example). According to Greaves & Maley (2012) cancer chemotherapy kills some tumor cells, but often creates chemotherapy resistant clones. Cancer Stem Cellsare of particular concern because these cells perform cancer initiating and propagating functions that are characteristics of metastatic spread from one location to another (Greaves & Maley, 2019). Most cancer deaths are caused by these spawned cells, therapeutically resistant to conventional treatments, that then colonize and disrupt the functioning of distant organs.

The part about cancer stem cells is accurate enough, as far as it goes, although I would point out that not everyone is completely down with the idea of “cancer stem cells,” preferring to view them more as a renaming of the long known heterogeneity of cancer cells, specifically the subpopulations that produce metastasis and resistance. Don’t get me wrong. The debate about cancer stem cells and their role in cancer progression and resistance is highly technical and complex, and I don’t want to oversimplify. I just mention it to point out that BenFen is overselling his point, which he continues to do with this paragraph:

An elegant series of experiments from the Riggin’s lab at Johns Hopkins University has demonstrated that physiological doses of mebendazole (fenbendazole) eradicated various forms of breast cancer, including triple-negative breast cancer, and, most important to this particular Substack article, mebendazole also was effective in reducing or eliminating distant organ metastases (Joe et al., 2022).

Let’s just say that the word “eradicated” is doing a lot of heavy lifting here, but let’s look at the specific reference, Joe et al, because it’s the one that BenFen cites most extensively. Let’s put it this way. Yes, the paper does show that mebendazole appears to have antitumor effects against TNBC in preclinical models, but it far from demonstrates that the drug “eradicates” TNBC, characterized by BenFen in the conclusion thusly:

There is a lot to unpack here but let’s not get off the main path: it certainly appears that there is overwhelming evidence that mebendazole (fenbendazole) eradicates cancer.

Notice something? BenFen keeps conflating mebendazole and fenbendazole as though they were the same drug. Although related, they are not the same drug; so BenFen’s citing a study about mebendazole as though its results would also apply to fenbenedazole is profoundly deceptive. Even alternative cancer cure advocates point this out:

For many years, scientists have been researching the anti-cancer benefits of benzimidazole anthelminthics, like mebendazole. The activity against gliomas was initially discovered accidentally when scientists noticed that mice, that were being treated with fenbendazole for pinworm infections, showed a resistance to the glioma grafts they were given. In other words, when the mice were taking fenbendazole, their bodies rejected the tumors that were injected into them! As astounding as this is, subsequent research showed much better performance with mebendazole and albendazole. Shortly after, two different studies showed extended survival in GBM animal models, up to a 63% increase in the average survival time.

In comparison, survival was not significantly increased in the animals treated with fenbendazole. This is probably due to low bioavailability and the fact that it does not cross the blood brain barrier well and therefore, cytotoxic doses do not accumulate near the cancer cells.

Previous cell studies show mebendazole inhibits glioma cells through disrupting microtubule formation. The drug binds to tubulin and prevents mitosis in the cancer cells. Subsequent animal and human studies have corroborated this. We do NOT have the same supporting data with fenbendazole!!

At the end of his post, after having cited all sorts of studies of mebendazole and simply equating it with fenbendazole, BenFen even admits:

Fenbendazole vs. Mebendazole vs. Albendazole vs. Flubendazole: The benzimidazoles are very similar chemically and they have very similar mechanisms of action with respect to disrupting microtubule function, specifically defined as binding to the colchicine-sensitive site of the beta subunit of helminithic (parasite) tubulin thereby disrupting binding of that beta unit with the alpha unit of tubulin which blocks intracellular transport and glucose absorption (Guerini et al., 2019). If someone asks you how fenbendazole kills the cancer cells, the answer is in italics in the previous sentence.

The class of drugs known as benzimidazoles includes fenbendazole, mebendazole, albendazole and flubendazole. Mebendazole is the form that is approved for human use while fenbendazole is approved for veterinary use. The main difference is the cost. Mebendazole is expensive ~$555 per 100 mg pill, while fenbendazole is inexpensive ~48 cents per 222 mg free powder dose (Williams, 2019). As you may recall, albendazole is the form used to treat intestinal parasites in India and these cost 2 cents per pill. FYI, to illustrate how Americans are screwed by Big Pharma, two pills of mebendazole cost just $4 in the UK, 27 cents per 100 mg pill in India and $555 per 100 mg pill in the US.

While most of the pre-clinical research uses mebendazole, probably because it is the FDA-approved-for-humans form of fenbendazole, virtually all of the self-treating clinical reports involve the use of fenbendazole. Because the preclinical cancer studies use mebendazole (ironically the human form of fenbendazole) and humans self-treat their cancers with fenbendazole (the animal form of mebendazole) it is very reasonable to assume that mebendazole and fenbendazole are functional equivalents with respect to cancer. It would be helpful if future investigations simply used fenbendazole as a practical matter. For the purposes of this Substack, fenbendazole, mebendazole and albendazole are used interchangably.

No, you can’t just assume that a related drug will be as effective as the drug you’re talking about. You just can’t. Sure, it’s not unreasonable to assume that fenbendazole probably has similar effects as mebendazole, but so many things could impact that based on the pharmacology of the individual drugs, including absorption, serum half-life, maximal achievable concentrations in the serum, toxicity profile, and so many other things. Heck, the investigators who published the study cited by BenFen used a delivery system that mixed the mebendazole with a special sesame oil carrier mixed with a high fat diet. They even speculated that increased bioavailability and absorption of the drug, thanks to this carrier, was why their results had been better than previously published results by another group.

None of this stops BenFen from proclaiming at the end of his post:

We have a cure for cancer. What is lacking is the courage and political will to apply that knowledge in an altruistic manner to help those who desperately can not wait.

In any event, nothing cited by BenFen about mebendazole actually demonstrates this. Antitumor activity against the cell lines examined? Yes. “Eradicating” TNBC? Not so much. A “cure for cancer”? Definitely not.

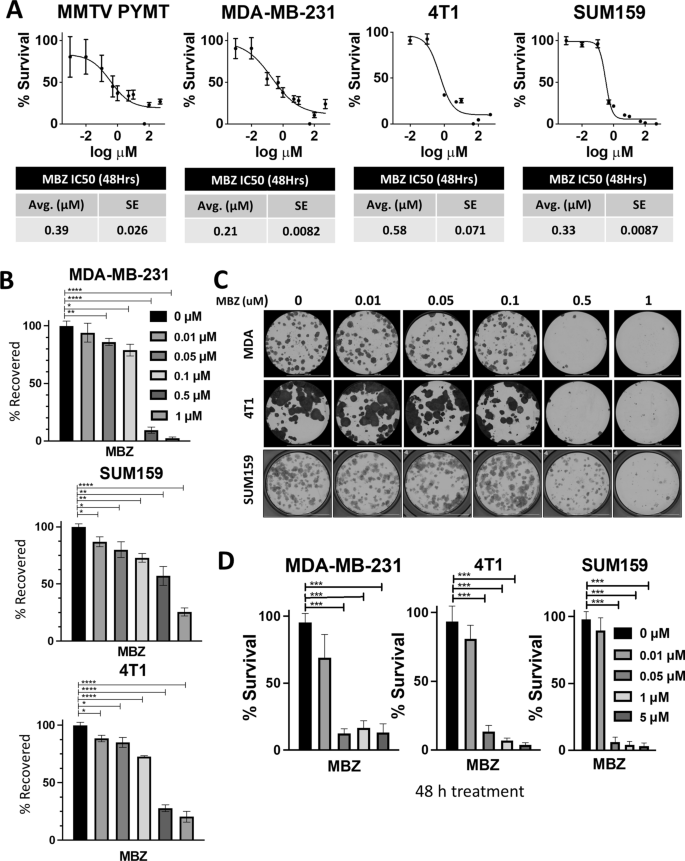

Take a look at what I mean in Figure 1. It’s OK; you don’t need to understand it all, just some of it:

I’m familiar with all of these cell lines and have extensively used the MDA-MB-231 cell line, a frequently used model for TNBC. The favorable finding in the figure above (panel A) is that mebendazole has an IC50 (the concentration that inhibits the growth of the cells by 50%) that is less than 1.0 micromolar (μM). That’s pretty good and within an acceptable range for further investigation. Panel B shows that only a percentage of the cells recover after a 48 hr treatment with mebendazole at various concentrations. One curious thing about Panel D that I noticed is this: Why did they leave out the 0.1 μM dose and go straight from 0.05 to 1 μM? That struck me as a bit odd, but whatever. Additional results shown in Figures 2 and 3 are that the drug decreases cell migration, inhibits cell cycle progression, and induces programmed cell death, all desirable traits for any anticancer drug.

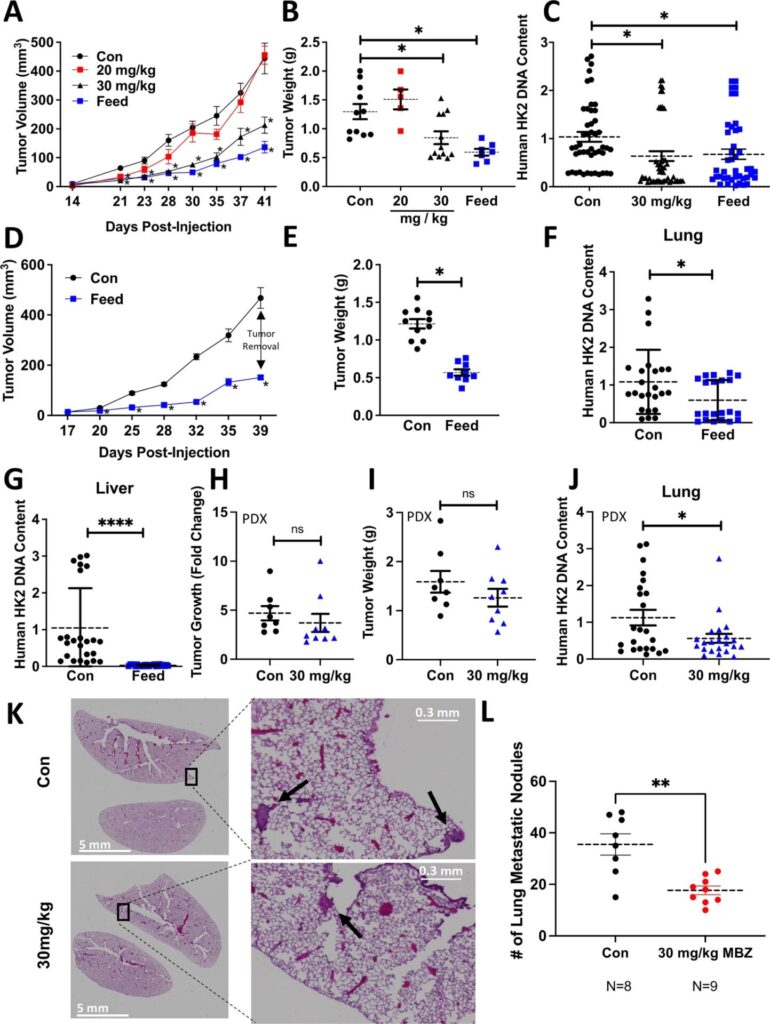

Now let’s look at Figure 4:

Panels A-C show how much varying doses of mebendazole mixed with the mouse feed inhibited the growth of MDA-MB-231 xenografts in NOD-SCID Gamma (NSG) immunodeficient mice. Figures G-J show how much the regimen decreased metastases to liver and lung, particularly liver, where it was very effective in preventing metastasis. (Figure 5 did basically the same experiments with 4T1, a mouse mammary tumor cell line that can be grown in immunocompetent mice.) Additional experiments show that the drug decreases the expression of genes associated with the cancer stem cell phenotype as well as indicators of the phenotype itself. All of these results suggest that repurposing the drug could be effective in humans, but not in the way the FenBen claims.

There’s just one problem. The drug tested is not febendazole. Indeed, a more recent study examining the effect of febendazole on breast cancer cell lines found that the IC50 for the drug for the MDA-MB-231 cell line is 10.5 μM, or over 100-fold—yes, 100-fold!—greater than the IC50 for mebendazole against this cell line in the study cited by BenFen. That is a concentration that would be very difficult, if not impossible, to safely achieve in humans.

The authors of the study put it this way (BC=breast cancer; MBZ=mebendazole):

TNBC is the most challenging BC subtype to treat and results in higher mortality due to the high incidence of metastatic cases and paucity of treatment options. Most patients with BC would survive their disease if metastasis could be prevented. Our preclinical results showed that MBZ reduced metastasis with no side effects in mice, and it is well tolerated in humans even at higher doses and for longer durations than used in mice [27]. Given this safety profile, MBZ is a candidate for long-term use and may have promise as adjuvant therapy following surgical resection to prevent BC metastasis. Future studies considering the addition of MBZ to the standard of care treatment are warranted in order to advance MBZ in clinical trials for patients with breast cancer.

This is the way most such drugs are tested and their usage advanced. Indeed, this podcast by BreastCancer.org featuring Brian Wojciechowski, MD discussing fenbendazole tells the tale in an easily understandable fashion. Particularly interesting to me was how scientists noted the “signal” that the drug might have antitumor activity:

What was happening a couple years ago, they did a study at Johns Hopkins. They had these mice that were completely immunosuppressed. They had no immune system, so these mice would be inoculated with tumors. Because there was no immune system, the tumors would grow easily in the mice, and then the cancer researchers could test various cancer drugs against these tumors. So were they testing fenbendazole against the tumors? No. Actually, the fenbendazole, because it was an anti-parasitic, was actually being given to the mice in their food…

…and they noticed that the ones that got the fenbendazole, the tumors wouldn’t grow. So then they started testing, you know, giving some mice fenbendazole, and some mice didn’t get fenbenzadole, and they found that there was a real signal there. The fenbendazole seemed to be helping to kill these tumors in these mice.

We also learn that fenbendazole is an inhibitor of microtubules, which is similar to a mechanism by which Taxol, for instance, exhibits anticancer activity. Does that mean fenbendazole works? No. Nor does it mean that it doesn’t work either. There is fairly promising preclinical evidence for fenbendazole and related drugs, but no good human evidence, and anecdotes of the sort promoted by BenFen don’t count.

What I like is how Dr. Wojciechowski tackles the granddaddy of all anecdotes for these drugs, which are often mixed together in protocol popularized by a man named Joe Tippens and is often referred to as the Tippens protocol, which in addition to fenbendazole included curcumin and cannabidiol oil. Mr. Tippens had a bad cancer and survived, attributing his good fortune to his protocol. Here’s what Dr. Wojciechowski says about it:

Yeah, so small-cell lung cancer metastatic is a devastating disease, and on average people live only about 9 to 12 months with that particular cancer. But every oncologist has seen a small percentage of people, say maybe 5%, who live up to 5 years with this disease. And there could be a lot of different reasons for that. Even within small-cell lung cancer, everyone is different, and everyone will respond to different treatments in different ways. So one possibility, of course, is that fenbendazole works. Okay? We can’t discount that possibility. The other possibility is that the other chemo drugs that he was on, which also have antimicrotubular activities — for example, Taxol, which has antimicrotubular activities just like fenbendazole, so if he was on that drug you have to ask, maybe it was the Taxol that did it, which has similar properties. It’s hard to know for sure. I’m not his doctor, and I don’t know the details of his case, but my patients ask me about these sort of things all the time. And I’m not going to stand in anyone’s way. I’m not going to say you can’t take X, Y, or Z medication. But on the other hand, people ask me for my advice based on my experience and expertise. And when patients ask me about these things, it usually goes something like this: Well, it hasn’t been studied in human beings, so we don’t know if it helps. But it’s almost as important that we don’t know if it’s harmful either. I would never want to recommend to my patients anything that I was uncertain about, especially when there are other medicines and treatments which do have good studies and we do have a lot of good data and information as to whether or not it helps and what the side effects are.

This is an excellent summation of the problems involved in interpretation of anecdotes like this. In addition, I found out something about Joe Tippens that I hadn’t heard before:

The fenbendazole scandal was an incident wherein false information that fenbendazole, an anthelmintic used to treat various parasites in dogs, cured terminal lung cancer spread among patients. It started with the claim of American cancer patient, Joe Tippens, but rather became sensational in South Korea. It caused national confusion and led to fenbendazole being sold out at pharmacies across the country in South Korea. Contrary to what the people know, however, Joe Tippens was a participant in the Kitruda clinical trial at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, and his improvement was likely to be the effect of immuno-cancer drugs.

Sound familiar? (Also, this is the same drug that was used in the KEYNOTE-522 protocol for TNBC.) Elsewhere:

There is still no comprehensive approach. And J keeps on going. It is important to note several things. J is on Keytruda as well. His oncologist at MD Anderson is unwilling to commit that it is the fenbendazole is making the difference.

Of course not. No responsible oncologist, much less one employed at one of the premiere cancer centers in the world, would conclude that fenbendazole is what “cured” Joe Tippens. Moreover, I note that it’s not straightforward to discover this information about Joe Tippens at all; I’ve only found a couple of sources thus far, and it took considerable Googling. (Same as it ever was.) Just go back to my section on the sorts of questions you need to ask whenever you see an alternative medicine cancer cure testimonial.

Fenbendazole: The new laetrile?

As I wrote this, I thought that maybe I had been too harsh on fenbendazole. By that I don’t mean that I think it could possibly produce the miracle remissions described in the anecdotes I’ve discussed. What I do mean is that the drug does have some preclinical evidence (e.g., this study published in November that showed activity against one kind of lymphoma in mice but not another and this study that showed activity against MDA-MB-231 cells) that suggests that it might be repurposed effectively to treat some cancers; it’s just that there is no human clinical trial evidence yet that I have been able to find. Laetrile, on the other hand, had a much sketchier level of preclinical evidence, as I recall. Indeed, preclinical studies failed to find any evidence of anticancer activity attributable to laetrile in mice. Of course, our friend BenFen has a built-in excuse for why even the mebendazole study that he cited wasn’t even more impressive:

(It is important to note that several of the experimental protocols used here were not optimized to kill all the TNBC cells, only to impair their growth or spread for the purposes of the specific experiment).

See? Scientists weren’t really trying, now, were they? I mean, if they were, they’d buy into BenFen’s speculation that the reason cancer rates in developing countries are lower than in developed countries is because so many of them have to take anthelminthic medications due to how common worm infestations are there. It couldn’t possibly be because the populations are younger and die more commonly of diseases not related to aging, like cancer, could it?

Still, I don’t think that the comparison is entirely unwarranted. Even if fenbendazole is found to have clinically useful anticancer activity in humans, it won’t be as a single agent. As Dr. Wojciechowski related, the next step in testing the drug would be to add it to known existing regimens to determine if its addition can improve outcomes; that is, after careful phase I testing in which the maximum tolerated dose in cancer patients is assessed. Further studies would be based on existing preclinical studies and a careful consideration of which make the most scientific sense to add the drug to.

Finally, I can safely make a couple of predictions. First, no single drug is a miracle cure for any cancer, which means that even if fenbendazole is validated in clinical trials against cancer it will not be prescribed as a single agent. Second, if fenbendazole is validated as an effective anticancer agent in clinical trials, its contribution to cancer survival will be incremental, not miraculous. I like to remember how in the 1990s, when I was but a wee graduate student and postdoc, angiogenesis inhibitors were touted as a near “cure” for cancer that would turn cancer into a chronic and manageable disease. (Truly, this was a heady time in the world of cancer research.) What happened instead is that Avastin (for example) produced an incremental improvement in results for some cancers when added to existing treatment regimens and didn’t work at all for others. That is the best that a science-based perspective would predict for fenbendazole; either that, or it doesn’t work in humans. Time will tell, but in the meantime these cancer cure testimonials are doing what such testimonials always do: Produce false hope in cancer patients.